In September 2018, I was fortunate to join the elite swimming club Olympique Nice Natation (ONN) as a strength and conditioning coach. Fortunate because this meant working with Fabrice Pellerin, one of the World’s most technical coaches. Fabrice trained athletes that won nine medals at the 2012 London Olympics. As the strength and conditioning coach, my primary task was to improve the strength levels of the swimmers leading up to the World Championships in late 2019 and the 2020 Olympic Games. As you can imagine, we had to adapt and adjust to certain constraints throughout 2020. In this article, I will give some background on the athletes, the demands of competitive swimming, and the philosophy of Fabrice. I will also lead you through the methods and programs used to develop the athletes’ performance inspired by our School of Strength, StrongFirst, which led to the team’s success at the Olympic level.

Background

Fabrice’s philosophy is based on providing his athletes with “the feeling of competence.” His goal is to give his swimmers the necessary tools (technical, physiological, and psychological) needed to assemble their technical, tactical, and physical puzzle come game-day.

In the swimming world, swimmers spend more time training than competing and Fabrice believes in the importance of establishing a clear difference between “training to perform” and “performing in training.” Rings a bell, doesn’t it? Fabrice naturally programs specific intensity training rather than volume training, waving the workload in every cycle much like we see in Plan Strong™. A typical elite swimmer swims a daily average of 12-14 kilometers, but Fabrice’s swimmers only swim 8-10 kilometers.

The distance this group swims in competition ranges from 50 meters to 400 meters, including various strokes such as the front crawl, the backstroke, the butterfly, and the medley (a combination of butterfly, backstroke, breaststroke, and front crawl).

To give you an idea of how fast these athletes swim, for men the typical 50-meter freestyle time is under 25 seconds, the 100 meters is under 50 seconds, and the 200 meters is swum under one minute and 50 seconds. The physical effort in these events includes both glycolytic and aerobic dominance. Physically, swimmers are slender and often hypermobile. They spend four to five hours a day in a gravity-divers environment, in a horizontal position, and with constant and direct feedback from the water (which means even in strength training they have an enormous need for kinesthetic feedback).

Upon my arrival, the team was divided into two groups. The younger group ranged from 16 to 22 years old, and the older group ranged from 22 to 30 years old. For the younger group, the main priority was basic athletic education. The older group was made up of multi-medalists in National, European, World, and/or Olympic competitions. This group already had an athletic background in the traditional sense. They had done many different elastic band rotations to work the rotator cuffs, pullups, pushups, machine guided retropulsion (such as the front crawl with the chest inclined forward), stretching, and foam rolling. These swimmers have an anthropometry specifically linked to their sport. They are tall with long limbs measuring 1.75m to 1.80m for the women and up to 2m for the men. These athletes have the capacity to produce mutant-like type efforts. I have witnessed multiple times how they create exceptionally high effort, as they would during the final heat at a World class competition and burn through their adaptative reserves for a long period of time.

To summarize, I am working with tall, slender, hypermobile athletes specializing in aerobic and glycolytic efforts in water who need to increase overall strength and the ability to coordinate it, while also staying fresh for their daily swimming sessions.

As Bryan Mills would say, “Good Luck.”

The Program

The first two-month cycle focused on building skills, assessing movement, and teaching fundamental kettlebell movements. It took place in two steps.

Step One: Structuring a Warmup, Posture-Development, and Assessing Movement Patterns

- Warm-up and Postural Development:

- Belly breathing, cat-camel, foam roller thoracic extensions, rib pull, and Brettzel stretch

- Forced breathing, biomechanical breathing, core breathing, StrongFirst plank, StrongFirst bridge, Dr. Stu McGill’s big three (the curl-up, side bridge, and bird-dog), hollow holds, pushups

- Kettlebell pull-over, halo, tall-kneeling halo, half halo

- Hip-flexor stretch, pump stretch, prying goblet squat

- Hang/suspension from a bar, scapular pullups, knee raises, leg raises

- Assessment of Movement Patterns:

- Training load assessment

- Completing Functional Movement Screen (FMS) and PRO FTS assessmentsComparing aquatic data observed by the head coach and avoiding correcting certain patterns that can be a strength in the water

- Designing corrective exercises for each swimmer individually

Step Two: Teaching the Fundamental Movements

Our first training cycle was quite simply based on Simple & Sinister. Throughout the two-month cycle, we took the time to learn and progress with the fundamental skills of the get-up and the swing. We also focused on how to correctly execute pulling movements as this is an important element in injury prevention, along with a proper articular alignment of the shoulder while engaging the midsection.

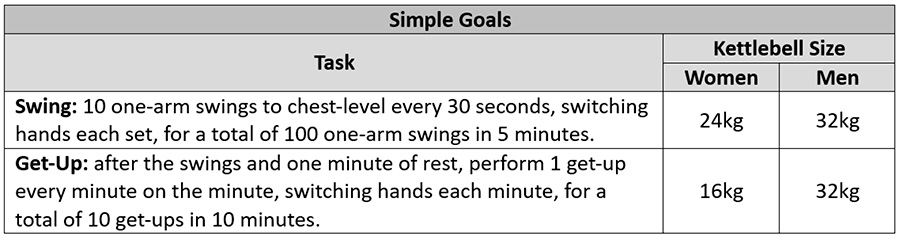

There were three objectives for the first training cycle. The first was to ensure that the movements taught met technical StrongFirst standards. The second was to have each athlete reach the “Simple” standards (shown in the table below).

- The Technical Learning Process:

- The goblet squat

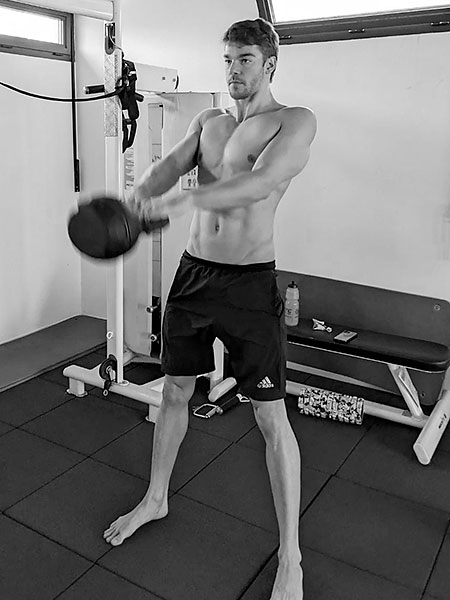

- The kettlebell deadlift, two-arm swing, one-arm swing

- The get-up

- TRX training: batwings, face pulls, Ts, Ys

And lastly, to establish proper hardstyle technique in the two-arm swing and goblet squat sequence: 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1. These objectives were generally met, and the following months were devoted to barbell and pullup instruction. It was also important to teach the swimmers about different types of repetitions (i.e., ladders) and the proper usage of the percentage of their technical rep max. The younger athletes worked for a longer period on the dumbbell version of the “Total Tension Kettlebell Complex” by Pavel.

Preparing for the 2019 World Championships in Korea

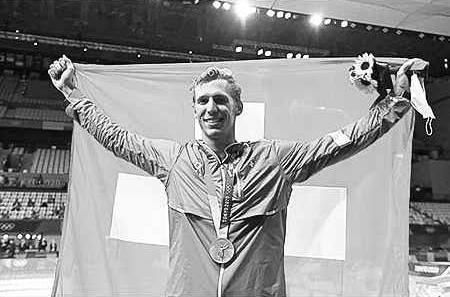

After more than nine months of solid work, we focused the last stretch of the preparation phase on the kettlebell swing and pushup using Plan Strong principles to design a variation of The Quick and the Dead protocol. Given that aquatic training increases in volume and intensity leading up to a major event, in which four of my athletes were participating, I chose this minimalistic approach of anti-glycolytic and explosive training. I began using this variation of Plan Strong and The Quick and the Dead two months before the championship and continued it up until a few days before it began. As proof of the effectiveness of this program one of the athletes, Jeremy Desplanches, an international Swiss swimmer, obtained the title of Vice-World champion in the 200m medley.

Preparing for the 2020 Olympic Games

Beginning in the first training cycle leading up to the games, I collected individual data on each swimmer and intentionally applied different training methods to note which one worked for each swimmer individually. By doing this, I could then use the most efficient/effective programs in the periodization training for the year leading up to the Olympics. Isometrics, hypertrophy, and glycolytic peaking were methods I only used briefly in two-week micro-cycles, planning to reintroduce them later and gain an extra “boost” when training them a second time.

Then, as we all personally experienced, everything came to a sudden and complete halt at the end of February 2020 with the arrival of the pandemic. The athletes were forced to take three months off and even with the efforts of installing remote training sessions, it was not easy to find a substitute for five-hour daily swimming sessions.

Training Resumed

When we resumed training in June of 2020, Fabrice and I decided that during the summer months the priority would be developing the swimmers’ athletic abilities— less swimming and more lifting weights. During the first two months, I introduced a cycle of hypertrophy based on the principles of Built Strong with four sessions a week. Some of swimmers gained quite a bit of muscle and improved their 25-meter sprint times. Then, I started a new approach by introducing the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) and repetitions in reserve (RIR).

To give some context, swimmers at this elite level are mutants. For example, here are some lifts of a swimmer at a 75kg bodyweight:

- 1RM Zercher squat: 150kg

- 1RM pullup: 52kg

- 1RM bench press: 100kg

Most swimmers can do 15 to 20 repetitions with 85{32c02201c4e0b91ecf15bfd3deecd875caca8b9615db42cfd45ce3d8de8d0829} of their 1RM with large individual variabilities. I chose to base training mainly on the targeted number of repetitions, RPE, and RIR.

At this point, the athletes had enough experience to gauge their RPE and RIR throughout their training sessions.

Here’s an example of a bench press session:

- 1 set of 5-8 repetitions: RPE 4, RIR 10

- 1 set of 5 repetitions: RPE 6-7, RIR 5-6

- 1 set of 5 repetitions: RPE 8, RIR 2-3

The Olympics (Finally)

With all the tools set in place, we were ready to start the preparation for the 2021 Olympic Games in Tokyo. After great results at the French National Championships in December 2020, four of our swimmers qualified for the European Championships and the Olympic Games.

During the training process, Fabrice had realized something about the swimmers. They were so extremely efficient in their swimming technique that at times it was difficult for them to access the energetic side of training. So, at his request, we chose a long training cycle targeting glycolytic and aerobic power.

The Glycolytic Cycle

I designed the following 8-week cycle:

- Three weeks of preparation following Strong Endurance™ protocols using four different exercises three times a week. The four exercises were dumbbell rows, kettlebell swings, med ball slams, and pushups.

- Two weeks with reduced rest time and gradually increased work time, doing specialized varieties of the exercises. The swimmers had a high capacity of adaptation, and the goal was to limit this.

- The last three weeks included one target session every Wednesday with the intent of “repeat until failure.” This specific session constituted the glycolytic peak of the cycle. Four exercises were executed in a circuit with a work-to-rest ratio of 1:3. In week one, the goal was to repeat this circuit the maximum number of times possible. The second week dropped to 70{32c02201c4e0b91ecf15bfd3deecd875caca8b9615db42cfd45ce3d8de8d0829} of this volume. In the third week, it dropped to 50{32c02201c4e0b91ecf15bfd3deecd875caca8b9615db42cfd45ce3d8de8d0829}. This created the peaking phase.

Peaking and Results

I developed individualized training programs for each swimmer during the last three weeks leading up to the Olympic Games. This mostly included mobility work and exercises to maintain their strength levels. Half of our group improved their personal swimming record during the Tokyo 2021 Olympic Games. Jeremy won the bronze medal in the 200-meter medley, achieved a personal record, and set a new Swiss National record. Another one of our swimmers, Charles Rihoux, achieved his personal best during the 4x100m freestyle relay. The athletes’ performance at the games reflected the training efforts of the whole team over the last few years.

Conclusion

The beautiful outcome of this final cycle, the medals won at French Nationals and at the European and Olympic level, and the positive feedback from the swimmers over the last three years have shown the effectiveness of StrongFirst training programs. I have been able to test the training principles of our School of Strength at the highest level of competition. Of course, strength training represents about two percent of the swimmers’ weekly training and is only a small piece of the bigger picture. Ninety-eight percent of the credit should be given to Fabrice and the athletes themselves. However, I am proud to have been able to use StrongFirst principles to make my contribution to their performance and success in the pool. The 2024 Olympic Games will be held in Paris. We are preparing a new generation of swimmers and the training cycle has already begun. StrongFirst principles remain an important guideline in my work as I design new training programs. There are many emotions involved in training and working with athletes. A win and a loss have a large influence on the decisions made during training and having strong and proven principles as a guideline is important. In addition, having the StrongFirst community, mentors, and friends to offer advice is priceless. If you are a strength and conditioning coach training athletes at any level, I recommend attending a StrongFirst workshop, certification, or special event. I can say without a doubt, it will help you become a better coach and contribute to the performance and success of your athletes.